- Home

- Tony Abbott

Firegirl

Firegirl Read online

Copyright © 2006 by Tony Abbott

Reader’s Guide copyright © 2007 by Little, Brown and Company

All rights reserved. Except as permitted under the U.S. Copyright Act of 1976, no part of this publication may be reproduced, distributed, or transmitted in any form or by any means, or stored in a database or retrieval system, without the prior written permission of the publisher.

Little, Brown and Company

Hachette Book Group USA

237 Park Avenue, New York, NY 10017

Visit our Web site at www.HachetteBookGroup.com

First eBook Edition: June 2007

The characters and events portrayed in this book are fictitious. Any similarity to real persons, living or dead, is coincidental and not intended by the author.

The Hachette Book Group Publishing name and logo is a trademark of Hachette Book Group, Inc.

ISBN: 978-0-316-05019-7

Contents

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Acknowledgments

Reader’s Guide

Find out what boarding school is really like!

Praise for Firegirl

* “Leaves a big impact.”

—Publishers Weekly (starred review)

* “This is a thoughtful exploration of a brief interlude’s lasting impact.”

—The Bulletin (starred review)

“In this poignant story, readers will recognize the insecurities of junior high and discover that even by doing small acts of kindness, people stand to gain more than they lose.”

—Booklist

“A touching story of friendship that is easy to read yet hard to forget.”

—School Library Journal

“Understated, beautifully written, and deeply moving, Firegirl is a book that young readers will treasure for its ability to illuminate the elements of the human spirit that we all have in common.”

—BookPage

“Prolific fantasy author Abbott has created a realistic wallflower struggling to bloom.”

—Kirkus

“It’s a beautiful story, a sad story, brilliantly written, a story you’ll never forget.”

—Newbery Honor winner Patricia Reilly Giff

“[A] powerfully moving achievement.”

—VOYA

Golden Kite Award Winner

Texas Bluebonnet Award nominee

For her

Chapter 1

It wasn’t much, really, the whole Jessica Feeney thing. If you look at it, nothing much happened. She was a girl who came into my class after the beginning of the year and was only there for a couple of weeks or so. Stuff did get a little crazy for a while, but it didn’t last long, and I think it was mostly in my head anyway. Then she wasn’t there anymore.

That was pretty much it.

I had a bunch of things going on then, and she was just one of them. There was the car and the class election and Courtney and Jeff. But there was Jessica, too. If I think about it now, I guess I would say that the Friday before she came was probably the last normal day for a while. As normal as things ever were with me and Jeff.

It was the last week of September. The weather had been warm all the way from the start of school. St. Catherine’s has gray blazers, navy blue pants, white shirts, and blue ties, and it was hot in our uniforms. I sweat most of those days, right through my shirt, making what some of the kids called stink spots under the arms. We weren’t allowed to take off our blazers in school, even when it was hot, so mine always got stained from the sweat.

Like most afternoons, I got off the bus at Jeff Hicks’s house. We jumped from the top of the bus stairs and hit the front yard running, our blazers flying in our hands.

“You ever smell blood?” he asked, half turning to me.

Jeff had been my friend for about three years, since the summer after third grade. As we went up the side steps to his house, I remember thinking that he asked me off-the-wall questions a lot.

“What?” I said.

Jeff always said some strange thing, then waited, and I would ask “what?” so he could say it again and make a thing about it. He reached the door first.

“Did you ever smell blood?” he repeated.

“What does that mean?” I asked.

“Sometimes my mom comes home from the hospital all bloody from the emergency room —”

We rushed through the side door, making a lot of noise in the empty kitchen. Jeff’s house was always unlocked, even though it had been empty all day.

“— some guy’s guts on her shirt,” he said. “It’s so gross. It’s the coolest thing. So, did you ever smell blood?” He yanked open the refrigerator door.

“I don’t know. Maybe. When I cut my finger —”

“That’s not enough. I mean a lot. A whole glass of the stuff.”

I felt my stomach jump a little. “A glass of blood?” I said. “Who has glasses of blood?”

He pulled out a tumbler of red liquid — blood? — from the refrigerator and began drinking. He drank and laughed and drank. I finally realized it was cranberry juice. The juice sloshed all down his chin and onto the front of his white shirt.

His shirt had little blots of red spreading down the front as he was dripping juice and laughing and watching me, until I laughed, too, at the whole thing.

“Stupid,” I breathed. “How long did you have that glass waiting in there?”

Laughing even harder, he put the dripping glass on the kitchen table and wiped his mouth on his cuff. “By the way, I went for a ride in it last night.” He went to the basement door and pulled it open.

I was still looking at the glass on the table. “Huh?”

He jumped down the stairs to a room with a TV and paneling. There were dark wooden shelves on the walls piled with stacks of his comic books.

I was right behind him. “You went for a ride in what?”

It was that game again. But I already knew.

“Duh. In your brain,” he said. “My uncle’s Cobra. I thought it was all you ever thought about.”

“Yeah? The Cobra?”

He snickered as he went to the shelves. “The Cobra.”

A Cobra is a classic sports car from the 1960s. I love Cobras. Not the skinny kind they made for a couple of years, but the fat one. You see them every once in a while. A Cobra is low and all curved and super-fat, like a chunky bug that’s pumped up like a balloon. It isn’t a family car. It’s just two seats, a steering wheel, and pedals on the floor. It’s a machine. The racing tires are really fat. The wheel wells over each tire flare out like big, angry lips. The front end of a Cobra looks like a snake, with two headlights like eyes and a big mouth (the radiator hole) that could suck the pavement right up into it. It’s the nastiest-looking fast car on the road.

I love Cobras. I’ve built plastic models of them. I’ve bought magazines about them. I once went to an auto show with my father, and they had a red racing Cobra there. The shine was so thick it seemed like if you dipped your finger into it; it would be hot and wet. But they wouldn’t let you get near enough to touch it. “As if it’s so hot it’ll burn you,” I remember telling my father. He laughed. Cruise nights at a drive-in restaurant in the next town sometimes had a Cobra, too.

That past spring, Jeff had told me his uncle had an original Cobra, and I was

totally floored. He had restored it from a used one he bought in New York, where he lives. I had never seen the car, but Jeff told me it was a red one.

“The kind you like,” he had said.

People don’t really talk to me much in school or notice me, not even adults. My mother says it’s because I don’t “get out there.” But Jeff and I had been friends for a long time. We never really said much to each other, but we did stuff almost every day. I always got his jokes, and I think he liked that. I remember feeling it was so cool that he knew I liked red Cobras.

Jeff had said his uncle sometimes brought it up to his house, and he got to ride in it. But I didn’t get why I had never seen the car.

“I’ve never even seen your uncle,” I said.

Jeff was flipping through a stack of comics he had taken down from a shelf. He chose one and slumped in a chair with it. He didn’t say anything.

“I don’t have an uncle,” I went on. “I don’t get the whole uncle thing. It’s just me and my parents. Neither of them had sisters or brothers.” He still didn’t say anything, so I just kept on babbling. “Uncles always seem like these guys who get to have all the cool stuff fathers never get to have.”

Finally, he dropped his comic into his lap and looked at me. “Yeah, well, my Uncle Chuck has a Cobra. And he’s coming over next weekend.”

I think my heart thumped really loudly. “Saturday? Next Saturday?”

He shook his head. “No, the weekend after. The ninth I think my mother said. Maybe we’ll drive over to your house in the car.” He pushed the comic book off his lap.

“Really?”

He got up. “My mom said she got me two Avengers and a Spawn, the one where he bites through to another world. But she hid them because I yelled at her. Let’s find them. I need to get all the school junk out of my head.”

“Really? You mean it about the car? The Cobra? You’ll come over and we can ride around in it?”

“Sure. Let’s check her bedroom.”

Chapter 2

Monday morning, I slid into my seat in Mrs. Tracy’s classroom.

It seems strange now to think that I didn’t know anything about Jessica Feeney then. She was only a few minutes away, and I had no clue that she even existed. I had spent most of Sunday sitting on my bed with my car magazines around me. The window let all the warm air in, and I remember wondering if it would still be warm thirteen days later when the Cobra came.

My seat in class was the first one in the first row by the hall door. It was odd that I was even in the first seat. Where you sat in all the classrooms at St. Catherine’s was alphabetical. In every year before, there were kids sitting in front of me. Bender isn’t usually the first name. Kids with last names like Anderson or Arnold or Baker were some of the ones who sat in front of me in fourth, fifth, and sixth grade.

Two years ago, a girl named Jennifer Aaron sat at the head of the first row. She probably always had that seat, I thought. But I also thought it was strange because I had heard that Aaron was a Jewish name from the Bible, and why would a Jewish girl be going to a Catholic school? When I told my mother about her, she said I should just go ask her. But I never did find out. Jennifer transferred to public middle school last year, and two girls from the other class, Tricia Anderson and Cindy Bemioli, were in front of me for sixth.

Jeff hadn’t been on the bus that morning, but he was already sitting in his seat next to me at the head of row two.

He didn’t say anything when I said “Hey.” He just sat there quietly and chewed his fingernails, which he did a lot, without thinking. I guessed his mother had driven him in because he missed the bus. She probably wasn’t happy about it and so they probably had a fight. Jeff seemed to get mad a lot more since his father went away. Usually, I just left him alone, and pretty soon he’d be okay.

Right now his head was bent to the side, and he was turning his fingertips in his teeth. His tie was loose around his neck, and his top shirt button was undone. I remember thinking that his mother must have washed his shirt over the weekend, or it was an extra one because there were no spots on it. Maybe they had a fight about the shirt, too.

His legs dangled out into the teacher’s area at the front of the classroom. Mrs. Tracy had asked him a couple of times already that year to reel his legs back in under his desk. He was stretching them out when she came in just then.

“Scoot your legs in, Jeff. Your slouching will curve your spine,” she said. “You’ll be a stooped-over old man by the time you’re thirty.”

She walked past and set down a pile of papers on the middle of her desk.

“Thirty is an old man!” said Jeff, taking his fingers out of his teeth and half looking around and laughing.

I snickered when I saw him joking. Maybe he was okay again.

Mrs. Tracy narrowed her eyes at him then smiled. “You’ll feel different when you’re that age….”

“I know,” he said. “I’ll feel old!”

“All right, all right,” she said, but the class cracked up anyway. Another busload of kids came in after the second bell rang. Melissa Mayer, who was sort of chubby like me, came in laughing with Stephanie Pastor, who looked a little like a boy if you saw her from the right side. Kayla Brown plopped a paper on the teacher’s desk then sat behind me. She was freckled and had red hair and was as small as the girls in fifth grade.

Rich Downing came running in and jumped into his seat behind Kayla as if he was trying to win a race. His jacket was under his arm, and his shirt was coming out in the back. When he tucked it in I saw the same little V-shaped rip at the top of the rear seam of his waist that I had seen for the last couple of weeks. I knew that Rich was trying not to eat as much so his pants wouldn’t tear on him, but it was happening anyway. The pants I was wearing that year were ones I had gotten last spring and that weren’t too tight, so I wasn’t in trouble yet. Like Jeff, Rich liked to crack jokes in class, but he was never as quick or as funny as Jeff.

Samantha Embriano came by and sat in the last seat of my row. She had black hair and a round face and eyebrows that almost met over her nose. She always said her last name together with her first name: Samantha Embriano. Samantha Embriano. It was always like that.

It would be like me calling myself Tom Bender. Hi, I’m Tom Bender. Tom Bender here. You just don’t do that. I think at first she said her name like that because there must have been a year or two when she shared the same first name with someone else in her class. Samantha Baker or Samantha Taylor. But she continued to say Samantha Embriano even though that was not true anymore. Now we all called her that. Samantha Embriano.

Just after first prayers, when everybody stood up and held hands together and prayed along with Mrs. Tracy — “Hold hands? No way,” Eric LoBianco said every time — I leaned over to Jeff.

“We’re on for next weekend, right?” I asked. “Not this one, but the next one?”

“Next weekend?” he said.

“The Cobra,” I whispered.

Jeff’s face unclouded. He smiled. “Yeah. My uncle’s coming over.”

I smiled, too. Yeah, he’s coming over and yeah, it’s going to be awesome. Mrs. Tracy was still fiddling with something, and I scanned the room. I knew that no one else in the class was going to be riding in an awesome red Cobra next weekend. Or probably ever.

As I was thinking this and watching the last of the bus kids get into their seats, my eyes finally came to the last seat of the last row.

Chapter 3

Courtney Zisky sat in the last seat of the last row. She was the girl who I thought could easily be in clothes catalogs. Someone should pick her to be in them, posing with one hand on her waist, which was just the right size, and the other one flung up behind her as she pretended to walk. She’d be wearing all new clothes — a T-shirt never worn until five minutes before and flip-flops and shorts with flowers on them. Maybe there would be a breeze blowing through her hair as she tossed her head back but turned just a little to look at you.

&nbs

p; Courtney was beautiful. She had dark, almost-black hair and her skin was sort of creamy white. She didn’t have freckles or the pimples and blotches that Darlene Roberts had, who was three desks in front of her.

Darlene might even have been pretty good-looking if not for that, but in a different way. Plus, Darlene sometimes squeezed her pimples in the lavatory. You could tell, because when she came back, the skin around them was suddenly pink, like the spots on Jeff’s shirt. You could also tell she was sad about her pimples and mad that she had them.

But Courtney was perfect. When I looked over, she was bending back up from putting something under her seat. A wave of hair went loose at that moment and fell from behind her ear across her cheek. It was like a splash of something. I almost looked away as if it were a private thing, but I didn’t. The ceiling light flashed right off her hair and made it shine like a wall of dark water or something. The shine of her hair amazed me, but that was just one thing. I also knew that the smell of it was awesome.

One day, late last year, in Sister Robert Marie’s sixth grade, I was able to move up a reading level because some of the books my mother kept pushing on me finally helped. My mom was so glad. And so was I, mostly because moving up that late in the year meant that no matter how badly I did, there wouldn’t be enough time to drop me back down again. I’d begin seventh grade on a pretty good level.

I wasn’t a good reader, at least not to begin with. All through first and second grade, and part of third, I was in the lowest group. My brain always used to switch letters around when I tried to read and the whole thing made no sense. And because St. Catherine’s classes were small, everybody knew you were in the dumb group. Maybe Courtney didn’t ever call it that, but whenever people moved up, Sister Robert Marie tried to make them feel better by announcing that they were moving up.

“I hope you’ll welcome Tom,” she said that day. “Tom Bender is moving up —”

“From the dumb group,” Jeff whispered loud enough for everyone to hear, because he stayed behind when I moved.

Anyway, last year, for a couple of weeks at least, I was at the same table as Courtney.

The Great Jeff

The Great Jeff Underworlds #1: The Battle Begins

Underworlds #1: The Battle Begins Superhero Silliness

Superhero Silliness Treasure of the Orkins

Treasure of the Orkins Queen of Shadowthorn

Queen of Shadowthorn The Knights of Silversnow

The Knights of Silversnow Underworlds #2: When Monsters Escape

Underworlds #2: When Monsters Escape Sorcerer

Sorcerer Danger Guys on Ice

Danger Guys on Ice Dream Thief

Dream Thief The Moon Scroll (The Secrets of Droon #15)

The Moon Scroll (The Secrets of Droon #15) The Coiled Viper

The Coiled Viper Pirates of the Purple Dawn

Pirates of the Purple Dawn What a Trip!

What a Trip! Moon Magic

Moon Magic Wade and the Scorpion's Claw

Wade and the Scorpion's Claw Incredible Shrinking Kid!

Incredible Shrinking Kid! Flight of the Blue Serpent

Flight of the Blue Serpent The Serpent's Curse

The Serpent's Curse Gigantopus from Planet X!

Gigantopus from Planet X! The Great Ice Battle

The Great Ice Battle Under the Serpent Sea (The Secrets of Droon #12)

Under the Serpent Sea (The Secrets of Droon #12) The Riddle of Zorfendorf Castle

The Riddle of Zorfendorf Castle Lost Empire of Koomba

Lost Empire of Koomba In the Shadow of Goll

In the Shadow of Goll Danger Guys

Danger Guys The Copernicus Archives #2

The Copernicus Archives #2 Lunch-Box Dream

Lunch-Box Dream Into the Land of the Lost

Into the Land of the Lost Cosmic Boy Versus Mezmo Head!

Cosmic Boy Versus Mezmo Head! The Crazy Classroom Caper

The Crazy Classroom Caper Quest for the Queen

Quest for the Queen The Sleeping Giant of Goll

The Sleeping Giant of Goll The Startling Story of the Stolen Statue

The Startling Story of the Stolen Statue Brain That Wouldn't Obey!

Brain That Wouldn't Obey! The Ha-Ha-Haunting of Hyde House

The Ha-Ha-Haunting of Hyde House In the Ice Caves of Krog

In the Ice Caves of Krog In the Ice Caves of Krog (The Secrets of Droon #20)

In the Ice Caves of Krog (The Secrets of Droon #20) Beast from Beneath the Cafeteria!

Beast from Beneath the Cafeteria! Mississippi River Blues: (The Adventures of Tom Sawyer) (Cracked Classics, 2)

Mississippi River Blues: (The Adventures of Tom Sawyer) (Cracked Classics, 2) The Hidden Stairs and the Magic Carpet

The Hidden Stairs and the Magic Carpet The Mysterious Island

The Mysterious Island Flight of the Genie

Flight of the Genie Voyage of the Jaffa Wind

Voyage of the Jaffa Wind Dream Thief (The Secrets of Droon #17)

Dream Thief (The Secrets of Droon #17) Danger Guys Hit the Beach

Danger Guys Hit the Beach Escape from Jabar-loo

Escape from Jabar-loo Zombie Surf Commandos from Mars!

Zombie Surf Commandos from Mars! Firegirl

Firegirl Underworlds #4: The Ice Dragon

Underworlds #4: The Ice Dragon Attack of the Alien Mole Invaders!

Attack of the Alien Mole Invaders! The Chariot of Queen Zara

The Chariot of Queen Zara The Isle of Mists

The Isle of Mists The Fortress of the Treasure Queen

The Fortress of the Treasure Queen The Moon Scroll

The Moon Scroll The Golden Vendetta

The Golden Vendetta The Tower of the Elf King

The Tower of the Elf King Crown of Wizards

Crown of Wizards Search for the Dragon Ship

Search for the Dragon Ship Wizard or Witch?

Wizard or Witch? Underworlds #3: Revenge of the Scorpion King

Underworlds #3: Revenge of the Scorpion King The Mask of Maliban (The Secrets of Droon #13)

The Mask of Maliban (The Secrets of Droon #13) The Summer of Owen Todd

The Summer of Owen Todd City in the Clouds

City in the Clouds Knights of the Ruby Wand

Knights of the Ruby Wand Danger Guys Blast Off

Danger Guys Blast Off Danger Guys and the Golden Lizard

Danger Guys and the Golden Lizard The Magic Escapes

The Magic Escapes Mississippi River Blues

Mississippi River Blues The Crown of Fire

The Crown of Fire The Golden Wasp

The Golden Wasp Voyage of the Jaffa Wind (The Secrets of Droon #14)

Voyage of the Jaffa Wind (The Secrets of Droon #14) Denis Ever After

Denis Ever After In the City of Dreams

In the City of Dreams The Moon Dragon

The Moon Dragon Revenge of the Tiki Men!

Revenge of the Tiki Men! The Hawk Bandits of Tarkoom

The Hawk Bandits of Tarkoom The Postcard

The Postcard The Copernicus Legacy: The Forbidden Stone

The Copernicus Legacy: The Forbidden Stone The Knights of Silversnow (The Secrets of Droon #16)

The Knights of Silversnow (The Secrets of Droon #16) Under the Serpent Sea

Under the Serpent Sea Voyagers of the Silver Sand

Voyagers of the Silver Sand X Marks the Spot

X Marks the Spot The Crazy Case of Missing Thunder

The Crazy Case of Missing Thunder Journey to the Volcano Palace

Journey to the Volcano Palace The Hawk Bandits of Tarkoom (The Secrets of Droon #11)

The Hawk Bandits of Tarkoom (The Secrets of Droon #11) The Race to Doobesh

The Race to Doobesh Trapped in Transylvania

Trapped in Transylvania Humbug Holiday

Humbug Holiday Goofballs 4: The Mysterious Talent Show Mystery

Goofballs 4: The Mysterious Talent Show Mystery The Mask of Maliban

The Mask of Maliban Final Quest

Final Quest The Genie King

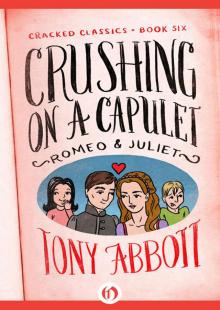

The Genie King Crushing on a Capulet

Crushing on a Capulet