- Home

- Tony Abbott

The Summer of Owen Todd

The Summer of Owen Todd Read online

Begin Reading

Table of Contents

About the Author

Copyright Page

Thank you for buying this

Farrar, Straus and Giroux ebook.

To receive special offers, bonus content,

and info on new releases and other great reads,

sign up for our newsletters.

Or visit us online at

us.macmillan.com/newslettersignup

For email updates on the author, click here.

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the author’s copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

For my family

ONE

You’ll hear things about me and Sean Huff. Whispers. Rumors. Lies. Weird talk you won’t understand. I get it. There will be stories and half stories for a while. People are people.

Sean was my friend. My best friend. And sure, he isn’t my friend anymore, but probably not for any reason you might come up with.

Shay, which is what I call him sometimes, and I got along like brothers from the very first. From the day of the Ping-Pong ball, the coffee cup, and the blood.

We were six, March of kindergarten, waiting for our moms in after-school. I didn’t know Sean yet, and I didn’t normally go to after-school, but it was weeks before my sister, Ginny, was born, so probably my mom was at her doctor. Anyway, the room was crowded with short chairs and round tables and buckets of blocks, stacks of coloring books, art easels with giant pads, cardboard building bricks. I’m just sitting there at a low table, drawing on a random pad and eyeing the clock over the head of Mr. Davis, a third-grade teacher, dying for my mom to come, when this kid with short brown hair and skinny arms sitting crisscross applesauce on the floor in front of the teacher’s desk dips his hand in a yellow beach pail next to him and stirs.

I can’t see what’s in the pail, but it clatters softly.

The kid has this sly look on his face, and while he’s stirring he wiggles his eyebrows at me as if to say, “Well…?”

I frown. With my face I say, “Well … what?”

He does the eyebrows again, then pulls his hand from the beach pail, and he’s holding a Ping-Pong ball between his fingers. With a big grin, he tosses it at my head. I swat it away. It dribbles to the floor.

“Enough of that, Sean,” Mr. Davis says, not lifting his nose out of whatever he’s reading at his desk.

But it’s not enough, not for this kid—Sean. He stifles a laugh and pulls a second ball from the beach pail. You have to understand that Mr. Davis can’t really see Sean because he’s on the floor squirreled up in front of the desk.

Well, this time I’m ready. I swing my drawing pencil back and forth like a baseball bat.

He pitches. I swing. It connects.

The ball soars up, over Sean’s head, over the top of the desk, and right into Mr. Davis’s coffee cup.

Coffee spurts, the teacher howls, and Sean bellows, “Hole in one!”

“That’s the end of that, you two!” Mr. Davis shouts.

But it’s still not the end.

Because Sean scrambles over to me on his knees and high-fives me with both hands. Since I’m still holding my pencil, I high-five him back with one hand, which goes between his two and smashes his nose, bloodying it, at the exact moment his mom and my mom walk into the room.

While Sean laughs and his lips and chin drip with blood, the screaming of the moms begins. This goes on for a while. Then, just before his mother takes him home, I beg my mom to have more babies so I can be in after-school more, and the laughing of the moms begins.

Since then, it’s pretty much been a done deal between Shay and me, and a lot of good stuff happened after that, but it wasn’t all fun. Maybe because of the way we met, the blood thing, you can see our lives together as a series of times we got banged up in one way or another.

In second grade, when we were eight, I was fooling around on my bike to cheer him up while his broken arm was healing when I fell off and sprained my ankle. In May near the end of third grade, he was diagnosed with diabetes and I nearly died of wasp stings. We were nine then. For years he’s had a faraway dad. There had been problems at home, and then his father moved away. Nothing like that for me, but for weeks when my grandfather was dying my mom lived with my grandma, and home without Mom was like having half a family.

Shay and I were also both born in February, so we were a couple of the oldest kids in each grade. He’s still kind of skinny and small for our age—I’m taller by three inches.

He was—is—so much smarter than me, it’s sometimes scary.

We did everything together, played whole long days by ourselves and cut across the six blocks between our houses pretty much every afternoon, until we didn’t.

I guess it’s not too much to say Sean still hates me for what I did. I used to cry about that, about the things he said to me, the words he threw at me. I still do. I don’t mind saying I cry. Tears aren’t everything or even anything. But it’s better this way.

At least he’s alive to hate me.

TWO

“Are you seriously getting taller?”

I laugh. “No. I don’t think so.”

It’s the second Saturday of June, eight in the morning. The day has opened bright and big and warm and still.

“Yeah, you are. You can probably see the Great Wall of China from up there.”

After the cold wet spring, summer has finally come to Brewster. It’s “moved in bag and baggage,” as my grandmother says. She once told me summer “has plopped its rosy-red bum” down on our long beach, “and ain’t getting up for nobody, no how.” Grandma is not for beginners.

“I don’t feel taller,” I say.

“You could be lying.”

“True.”

So. Brewster.

If Cape Cod is in the shape of your left arm bent at the elbow, with your hand and fingers curled at the tip, you can find Brewster between the bicep of Dennis and the inside elbow joint of Orleans. Sean and I have lived our whole lives here.

“No. I mean it.” He skims his flat hand from the top of his head to the tip of my right ear. “Is this even legal?” He makes a face, looks me up and down, and groans. “I thought you were my friend.”

We’ve just come out onto the baseball field behind the Fish House, a restaurant my parents and his mom go to mostly without kids. Coach called an “emergency” practice before our game later that morning—“emergency” because we played like babies the last two games, not hitting, and missing or dropping all the pop flies, flubbing the grounders—not the ones to me, of course, but all in all, we stank.

Our moms dropped us at the field and fled, probably for coffee. They’ve been friends since the Ping-Pong ball incident. It’s like we’re all bonded by Sean’s bloody nose.

Because of the summer tourist swarm—plague, my grandmother calls it—natives get crazy busy on the Cape helping all the strangers relax. From Memorial Day to Labor Day there’s no rest for grown-ups, which I guess is one reason for what’s going to happen this summer. Most people think Cape Cod is not real, that it’s just restaurants and beaches and summer theater, but that’s only because they come and go and don’t see anything. Real stuff happens here.

Just now there are lots of squeaking, slamming doors, and some cars drive off, raising dust, while some stay parked at angles to the field, spirals of sunlight blooming on their hoods.

I stretch my arms, wiggle inside my T-shirt. It’s not tight, but not loose, either. “Everything st

ill fits, I guess. My sneakers, my pants. My mom says I’ll get another inch soon, though. Maybe more.”

My mother actually does believe I’ll grow this summer, as if I’ve been holding my breath all the way through fifth grade and will finally let go. At the Memorial Day parade two weeks ago, she said I was “so poised” for a “growth spurt” and would gain an inch or two soon. She puts on a sad smile when she says things like that. I guess it means I’m growing up? I don’t know. I keep stretching, but I don’t feel it coming.

“And what’s the air like up there?” Sean asks.

“Ha. I think the Fish House just got a delivery.”

He sniffs. “I smell rain.”

You have to understand. The Cape is a narrow strip of land, an island, really, and, despite what my grandma says, weather doesn’t stay all that long. The air can be dry and clear and the sky as blue as blue glass, all for an incredible moment. Then things can change. Like right now, for instance. Behind the field to the west is a band of trees whose tops stand almost frozen against the blue, but over their bushy heads I see shadows of cloud.

I set the bat bag against the end of the bench that sits alongside the first-base line, but the bag slides loosely to the ground and the bats clink and ping as they settle.

Shay slumps onto the bench. “I seriously might be losing height. They’re gonna bounce me back to Eddy in the fall.”

Eddy Elementary is for Brewster kids, third to fifth grade. Once school lets out on Thursday we’ll head over to Nauset Regional Middle in September for sixth.

“You know, right? That my aunt moved?” he says. “Well, she did and two seconds later my mom goes out and finds me a…”

Kyle Mahon trots by, says, “Hi. You guys okay? Ready to win?”

We answer, “Yeah,” and “Or something,” and he slips a bat out of the bag and hustles, laughing, to home plate, where the coach is tossing balls out to the fielders.

I never aimed for that coffee cup, of course, and I couldn’t do it again if I tried, but baseball is one of only two things I do even half well. Not as good as Kyle. He can play any position on the field, is a solid hitter, and is the only reason Coach doesn’t quit and move away, which he’s told us, like, a hundred times he would do if Kyle weren’t on the team. Me? I can field all right, but I really love how slow the game is, as quiet and lazy as church on the hot Sundays in August. Standing crouched under the sun, not moving, anticipating the pitch, your feet planted in the grass of the field, looking around, waiting, watching with your shaded eyes, all of which is, face it, most of what anyone ever does in baseball—that’s when time almost stands still.

Almost.

Then something happens.

“What did she get you?” I ask. “Your mom. What did she get you?”

Sean shakes his head, grumbles. “Never mind. It’s freakish.”

I glance at the batter’s box. Kyle is swinging slowly as he waits for the ball. He has such good form, steady and natural. There’s more waiting. The kid pitching, he’s new to the team and stretching his neck from side to side, loosening up or pretending he is, taking his time.

We have a minute before the coach calls either of us to the plate.

“Tell.”

“A babysitter,” he says.

“A b-b-b … that is freakish. What do you need a sitter for? Are you pooping in your pants again?”

He makes a sound, blowing out a fruity breath between his lips.

“My mom got a job running a shop in P-town”—what we call Provincetown, about an hour away at the curled fingertip of the Cape—“a pretty great job. She’s been looking forever. Your mom must have told you. They talk a lot.”

They do.

Mrs. Huff is a tall lady, short jagged hair, always kind of hovering over Sean, nervous, I guess, distracted, and doesn’t smile all that much. She worked a long time as office secretary at Monomoy High School, which was good because she had the summers and afternoons off, but she left there a few months ago. She still always dresses like she’s going out. Not like my mom, who’s much more slowgoing and artsy and isn’t nervous at all and is always hugging Ginny and me, which I guess I could use a little less of.

I shrug. “I don’t think my mom told me.”

“So since my Aunt Karen moved and because of Mom’s new job and my ‘you-know,’ she says she had to find a ‘responsible individual’ right away to torment me.”

Sean’s “you-know” is his diabetes. He wears an insulin pod attached usually to his side under his shirt or sometimes on his arm like a jogger’s iPod. It’s small. He also has to prick his finger to check his blood sugar a few times a day and sometimes adjust the pod to shoot more or less insulin to compensate for what he’s going to eat. He can do pretty much anything anyone else can, and you’d never know except sometimes his breath is sour, sometimes fruity. That’s part of it.

I think back. His aunt has sat for him since his dad moved out and when his mother had to work late at the high school. I guess this new job means his mom won’t be around as much. This will be the first time he’s had a regular sitter who wasn’t a relative.

“A sitter,” he grumbles. “A babysitter. Which they really need to come up with a better name for.” He stomps his feet in the dust under the bench. He’s mad, but who wouldn’t be? He’s eleven, basically in sixth grade.

I try to be funny. “Watcher, maybe. Or a handler?”

“Handler, ick. I do like servant,” he says. “I could go with that. Oh, servant, fetch me that thing.”

“So who’s the lucky sitter? A nice high school girl?”

“Don’t I wish. No. His name is Paul. A grown-up guy. Paul Landissss.” He hisses out the name with a slither. “My mom met him at church, interviewed him and everything.” Old Sailors Church is where both our families go.

“A church guy. Not the deacon with the wart! Is he crusty old? Like a grandparent? What old man wants to be a sitter?”

“No, he’s young. Ish. Older-brother type. Out of college. You’ve probably seen him at church. He has a girlfriend. He’s okay, I guess. She had me meet him, but it was mostly them talking so, you know, whatever. Mom has to quit the choir because the new job has real long hours. He’s some kind of student, taking night courses somewhere, so he has plenty of time. He used to be an EMT and saved somebody’s life.”

“Maybe he can save you from choking on sugar cubes.”

“Funny, really. I told her please get a high school girl. I promised her nothing’s going to happen, that I’m saving myself for marriage. That’s a joke. She didn’t like it. ‘No,’ she said, ‘I’ll be gone for hours sometimes, and someone has to see you do your stuff right.’” Sean snorts. “As if I don’t know how after three years.”

It’s actually only two. It was third grade when he was diagnosed. We’d been running around at recess and when we went inside he suddenly got all wobbly. The next thing you know, he nearly crashed into a wall, said, “I feel … I feel…” went white, and started throwing up in the hallway. A teacher said, “I’m calling your mother!” Sean threw up again outside the nurse’s office when I got there with him.

“Sorry,” I say. “That’s tough.”

“Eh. The sitter’s a little bit of a chubbo. Plus he does a lot with coffee hour at church, sets it up and stuff.”

“Which is maybe how he became a chubbo?”

Shay laughs. “You’re lucky you don’t need a watcher.”

True. When my grandpa was sick, my mother cut down to part time at the newspaper—she did the arts calendar and wrote articles about concerts. She quit altogether when he was dying and hasn’t started up again, though she keeps talking about it. She liked it there. Now, she makes crafts that she sells and does volunteer work at a couple of places. Besides, my grandmother watches me and my sister, Ginny, when no one else can. Grandma drives from Hanover, where she lives. It’s over the bridge a little more than an hour from here. Ginny’s five. Mom promises I can start sitting for her after I turn twe

lve.

“You could come to the track tomorrow after church,” I tell him.

The track.

Go-karting is the other thing I do well. My father and my Uncle Jimmy own J&D Karts in Harwich, and it’s the longest running track on the Cape. In summer the business triples, quadruples even. The first few days after Memorial Day it’s all right for the natives. You can usually get in a few races. Then the plague begins. It’s all tourists until Labor Day. Cape Cod is built on holidays.

“I can’t,” he says. “I’m actually going to church with the guy tomorrow. It’s already all set up. Then my mom wants me to do yard work. Great, huh? Church and chores? It’ll be my first time with this strange dude and none of it will be fun and I’m going to be with him all day long. ‘With Paul.’ She says it like that.”

“With Powl,” I mock. “Powwwwl.”

He snorts a laugh. “Yeah. Powwwwl Landisssssssssss…”

THREE

Old Sailors Church is a tall, white wooden structure a little down Route 6A from the Fish House.

I have to say, we don’t go to church all that often, and it’s already planned that Dad and I will go to the track on Sunday, so it’s probably a surprise to everybody, even Ginny, when I ask if we can squeeze Old Sailors in before we go. I want to take a look at this new guy, and because of Mom, Dad can never refuse to go to church, even if it means getting to the track a bit later, so we go.

In the car on the way, I tell them about Sean and his babysitter.

“I’m so glad Jen has a full-time job, a good one,” says Mom.

“I know Paul,” my dad adds as he drives into the church lot. “He does coffee hour, doesn’t he? Owen, we can’t really stay for that.”

“I know,” I say. “After communion, zip, we go.”

“Ginny and I will get the full scoop before we walk home,” Mom says.

Ginny grins. “Scoop? Ice cream? At the General Store?”

“That, too.”

When we do get to church, it’s late, and the first reading is just over. I give a little wave as we pass Sean, who’s in a back pew. He raises his hand like a gun to his head, smiles a fake smile. I want to check out the man kneeling next to him, but his face is buried in the prayer book, and I have to follow Ginny and my mom to catch up with my father, who’s scooted up front. Dad thinks that by rushing into our seats, we’ll somehow get out earlier. Never mind that right after communion he and I’ll slip out, anyway.

The Great Jeff

The Great Jeff Underworlds #1: The Battle Begins

Underworlds #1: The Battle Begins Superhero Silliness

Superhero Silliness Treasure of the Orkins

Treasure of the Orkins Queen of Shadowthorn

Queen of Shadowthorn The Knights of Silversnow

The Knights of Silversnow Underworlds #2: When Monsters Escape

Underworlds #2: When Monsters Escape Sorcerer

Sorcerer Danger Guys on Ice

Danger Guys on Ice Dream Thief

Dream Thief The Moon Scroll (The Secrets of Droon #15)

The Moon Scroll (The Secrets of Droon #15) The Coiled Viper

The Coiled Viper Pirates of the Purple Dawn

Pirates of the Purple Dawn What a Trip!

What a Trip! Moon Magic

Moon Magic Wade and the Scorpion's Claw

Wade and the Scorpion's Claw Incredible Shrinking Kid!

Incredible Shrinking Kid! Flight of the Blue Serpent

Flight of the Blue Serpent The Serpent's Curse

The Serpent's Curse Gigantopus from Planet X!

Gigantopus from Planet X! The Great Ice Battle

The Great Ice Battle Under the Serpent Sea (The Secrets of Droon #12)

Under the Serpent Sea (The Secrets of Droon #12) The Riddle of Zorfendorf Castle

The Riddle of Zorfendorf Castle Lost Empire of Koomba

Lost Empire of Koomba In the Shadow of Goll

In the Shadow of Goll Danger Guys

Danger Guys The Copernicus Archives #2

The Copernicus Archives #2 Lunch-Box Dream

Lunch-Box Dream Into the Land of the Lost

Into the Land of the Lost Cosmic Boy Versus Mezmo Head!

Cosmic Boy Versus Mezmo Head! The Crazy Classroom Caper

The Crazy Classroom Caper Quest for the Queen

Quest for the Queen The Sleeping Giant of Goll

The Sleeping Giant of Goll The Startling Story of the Stolen Statue

The Startling Story of the Stolen Statue Brain That Wouldn't Obey!

Brain That Wouldn't Obey! The Ha-Ha-Haunting of Hyde House

The Ha-Ha-Haunting of Hyde House In the Ice Caves of Krog

In the Ice Caves of Krog In the Ice Caves of Krog (The Secrets of Droon #20)

In the Ice Caves of Krog (The Secrets of Droon #20) Beast from Beneath the Cafeteria!

Beast from Beneath the Cafeteria! Mississippi River Blues: (The Adventures of Tom Sawyer) (Cracked Classics, 2)

Mississippi River Blues: (The Adventures of Tom Sawyer) (Cracked Classics, 2) The Hidden Stairs and the Magic Carpet

The Hidden Stairs and the Magic Carpet The Mysterious Island

The Mysterious Island Flight of the Genie

Flight of the Genie Voyage of the Jaffa Wind

Voyage of the Jaffa Wind Dream Thief (The Secrets of Droon #17)

Dream Thief (The Secrets of Droon #17) Danger Guys Hit the Beach

Danger Guys Hit the Beach Escape from Jabar-loo

Escape from Jabar-loo Zombie Surf Commandos from Mars!

Zombie Surf Commandos from Mars! Firegirl

Firegirl Underworlds #4: The Ice Dragon

Underworlds #4: The Ice Dragon Attack of the Alien Mole Invaders!

Attack of the Alien Mole Invaders! The Chariot of Queen Zara

The Chariot of Queen Zara The Isle of Mists

The Isle of Mists The Fortress of the Treasure Queen

The Fortress of the Treasure Queen The Moon Scroll

The Moon Scroll The Golden Vendetta

The Golden Vendetta The Tower of the Elf King

The Tower of the Elf King Crown of Wizards

Crown of Wizards Search for the Dragon Ship

Search for the Dragon Ship Wizard or Witch?

Wizard or Witch? Underworlds #3: Revenge of the Scorpion King

Underworlds #3: Revenge of the Scorpion King The Mask of Maliban (The Secrets of Droon #13)

The Mask of Maliban (The Secrets of Droon #13) The Summer of Owen Todd

The Summer of Owen Todd City in the Clouds

City in the Clouds Knights of the Ruby Wand

Knights of the Ruby Wand Danger Guys Blast Off

Danger Guys Blast Off Danger Guys and the Golden Lizard

Danger Guys and the Golden Lizard The Magic Escapes

The Magic Escapes Mississippi River Blues

Mississippi River Blues The Crown of Fire

The Crown of Fire The Golden Wasp

The Golden Wasp Voyage of the Jaffa Wind (The Secrets of Droon #14)

Voyage of the Jaffa Wind (The Secrets of Droon #14) Denis Ever After

Denis Ever After In the City of Dreams

In the City of Dreams The Moon Dragon

The Moon Dragon Revenge of the Tiki Men!

Revenge of the Tiki Men! The Hawk Bandits of Tarkoom

The Hawk Bandits of Tarkoom The Postcard

The Postcard The Copernicus Legacy: The Forbidden Stone

The Copernicus Legacy: The Forbidden Stone The Knights of Silversnow (The Secrets of Droon #16)

The Knights of Silversnow (The Secrets of Droon #16) Under the Serpent Sea

Under the Serpent Sea Voyagers of the Silver Sand

Voyagers of the Silver Sand X Marks the Spot

X Marks the Spot The Crazy Case of Missing Thunder

The Crazy Case of Missing Thunder Journey to the Volcano Palace

Journey to the Volcano Palace The Hawk Bandits of Tarkoom (The Secrets of Droon #11)

The Hawk Bandits of Tarkoom (The Secrets of Droon #11) The Race to Doobesh

The Race to Doobesh Trapped in Transylvania

Trapped in Transylvania Humbug Holiday

Humbug Holiday Goofballs 4: The Mysterious Talent Show Mystery

Goofballs 4: The Mysterious Talent Show Mystery The Mask of Maliban

The Mask of Maliban Final Quest

Final Quest The Genie King

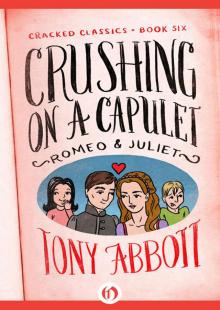

The Genie King Crushing on a Capulet

Crushing on a Capulet