- Home

- Tony Abbott

The Summer of Owen Todd Page 7

The Summer of Owen Todd Read online

Page 7

The papery petals smell different than regular roses do. An open beach rose is an amazing thing. It’s rained on, blown on, sunned on, and all the while gives out its scent. By the end of the summer the petals will have flown away and turned brown and disappeared into the grasses and down along the path to the cars.

“Have you ever sniffed both colors to see if there’s a difference?” I ask stupidly, but he doesn’t answer anyway. “I think pink are a little sweeter.” I lean over to one, then the other. “I like the white ones—”

“There’s probably no difference.” He looks at the water. “Come on. There’s not a lot of time.”

“We have the rest of the day,” I say, but he steps past me down the steep dune toward the flatness of the sand. A red umbrella flashes open to my right, and a girl laughs. I feel cold in the sunshine. My blood runs chilly, and my neck hurts.

“Are you coming?” he asks, half turning his head.

Is he going to wreck it for me?

I try to remember standing in the grass at center field just this morning, try to remember how light I felt and how calm. But just like on the field, I feel that the peace here could be broken so easily. Stealing a glance back at my mother, beach umbrella tucked under her arm, lugging a bulging beach bag, I want to run back to help, but she smiles and says, “Go on!” and Sean’s still looking at me. So I take a breath and follow him over the crest and down to the sand.

At the bottom of the dune you can look right and left on this long inward curve of beach and you feel right at the handle of a bow. I think the tide is coming in, but the flatness goes out a long way, a calm white sheet.

Sean suddenly takes off, kicking the sand in front of him as he approaches the water, then dragging his feet. Is he playing or angry?

“Owen?” my mother calls from the crest. She nods to her left. “Let’s set up over there.” There are only a few people, three or four towels, and some giggling girls fooling with a Frisbee. It’ll be quieter. Mom loves the quiet.

“Sean!” I call. He half turns, his hair flying in the breeze off the water. He’s smiling, which surprises me. I tilt my head to the left. “Yonder!”

He spins twice around on his heels and slogs happily through the sand like it’s snowdrifts. I think I can breathe again.

We dump our stuff: towels, his snack cooler, beach bags, folding chairs, baseball caps. We pop off our sneakers and trot back to help my mother with the last of the gear. In minutes, we’re set up.

“Let’s walk,” I say.

“Honey, you need lotion, both of you do,” Mom says. “Sean, do you need to eat? It’s half past twelve.”

“When we come back from our tour.”

“Fifteen minutes. I’ll time you.”

We circle the sandbar, not talking for a bit. The sand is littered with shells. The tide is definitely coming in and there’s less sandbar now than I saw from the top of the dune.

“Those guys charge so much,” he says out of nowhere.

“What guys?”

“The crushed-shell people. They come down here and collect shells for free and stomp on them and put them in bags and sell them to you. What a scam.”

“It’s probably more complicated.” I picture him standing alongside my garage, staring out to my driveway. I try to think of anything else than how he tricked me, but I can’t. I want to say something, but it would be so tense. I don’t.

Sean grins “Did I tell you—” Suddenly a red blade slices his face.

“Ahhh!” he screams, clutching his nose. Then he looks at his hands. Nothing. His nose is fine. “What the—” A Frisbee is lying in the sand at his feet.

“Sorry!” a little girl shouts, running to us.

“She’s sorry!” her friend says, also running. “OMG. So sorry!”

They must be six or seven and sparkling with sand, one with crazy red hair, the other with wet brown hair tied in a messy ponytail.

I snatch up the Frisbee. “This is a lethal weapon.” They freeze in their tracks as if they think I’m serious or they don’t know what the words mean. I make it worse. “You could have killed him.” They look back at their blanket, but it’s empty; their mothers or whoever are down at the water, dipping their toes in.

No help from them.

One girl’s face goes as red as her hair. “But we’re sorry.”

“It’s okay,” Sean says with a laugh. He takes the Frisbee from me and bops it lightly on the ponytail girl’s head.

She laughs nervously, steps back, puts her hands on her hips. “Want to play with us?”

Her friend slaps her arm. “No!”

I shake my head. “No, thanks.” But Sean turns bizarre.

“We better not. My friend here is just out of jail and can’t be with people just now. Jail’s why he knows what a weapon is.”

They both step back as if tied together.

“What? Liar!” I say.

Ponytail girl turns. “You boys are creepy. Both of you.” They each jump back a few more steps and plop down on the sand, staring at us.

“We want our Frisbee back,” says red hair. “Or we’ll tell.”

“Just a sec!” Sean runs backward, curling his arm around the Frisbee. “Owen, go out long. Let’s replay the play we did on the field this morning!”

I laugh inside, since “going out long” is football, but I spring back anyway and splash along the water line up to my ankles, looking over my shoulder. He slings the disk. It’s fast but low and dropping. “I got it!” I dive, right arm out, fingers reaching, and I clutch it, rolling over on my back in the sand and onto someone’s beach blanket and into some plastic bottles. “Ow! Ow!”

But I quickly jump up, holding the Frisbee high. “Did you see that? Did you see that? Let’s go to the video!”

The girls are screaming, but also laughing, I think, and Sean is laughing, too. “You have mustard on your butt!” he yells at me, and the girls scream louder when they hear the word. I toss them their Frisbee. They run away while Sean jumps around waving his arms. Is he okay again? I love it. He’s back and he’s normal.

“Hey!” Some middle-aged guy in red trunks that are too small for him hustles over to the blanket I trampled.

“Uh-oh,” I say.

Sean stops jumping and watches the man with red trunks reach his blanket, shake his head at what he finds, then flop onto it. Something crashes in Sean, I don’t know what. “I have to eat something.” He says this quietly.

“I have some mustard on my butt. You could…” I don’t go anywhere with that because it’s gross. I try to laugh, but I can’t.

“I have to eat,” Sean says again as if he didn’t hear me, which he did.

I don’t know exactly what just happened, but something buzzes in my chest.

* * *

Mom is reclining under the umbrella. It’s a big one and Sean fits neatly under it, while I decide to sit on the open blanket. Mom didn’t see our episode with the Frisbee or my fall on some guy’s mustard, so I don’t get the third degree.

“Lotion up,” she says. “Everybody.”

I do. I can take the sun pretty well, but I’ve gotten burns before that I don’t want to repeat. Sean will probably stay under the umbrella. He burns easily. I put on my J&D Karts cap, slop some lotion on my shoulders, and sit, hugging my knees on the blanket in the sun. Sean opens his beach bag, takes out his test kit, pricks his finger, tests his blood, presses a button on his controller unit, and eats.

“Do you feel the insulin going in?” my mom asks.

“Nah. It’s all timed out.”

I pricked myself once and did a reading, but his mother got mad because my number screwed up the download of his numbers. Anyway, I’m not hungry now, so I just sit. Mom opens a book but doesn’t read it. Instead she gets up and takes a plastic pail from her big bag. “Shells,” she says, and goes by herself to the disappearing sandbar.

“What do people do with them anyway?” Sean asks after she leaves. “I mean, I know what

driveway guys do and what your mom does, but everyone else who collects shells at the beach. Don’t you just end up throwing them away?”

“I don’t know.”

My mom makes shell lamps. In fact, she’s making a few for Mrs. Huff, who’ll display them at her shop as a sideline. Shell lamps have clear glass bases that you fill with shells or beach glass and some sand. Mom has made some for us and sells others on consignment, which means she gets paid only when they actually sell. They’re priced a few dollars more than an empty lamp, but they’re so beachy that people like them.

“It’s not a scam,” I say. “To make beach lamps. There’s the labor and the price of the lamp, so, you know…”

“I know. I wasn’t saying that.” He’s getting quieter under the shadow of the umbrella.

Time passes. The beach is crowding up a little more now that it’s afternoon and the tide is pressing in. More people bound past our setup, some with little on, teenage girls’ thin shirts darkened by the shapes of the suits underneath, boys’ chests bare and baggy shorts worn low. One girl with long black hair walks slowly by about ten feet away from our blanket.

“She should be your sitter,” I whisper. “Man!”

“Listen,” he says.

“In fact, I’m going to ask her. Wait here.” I pretend to start to get up when he jerks up to a crouch.

“Listen, I…”

But Mom is back, one hand holding her pail full of shells, the other cradling her cell phone to her ear. “Linda,” she says, setting the pail next to her beach chair and moving off again. “Yes? All right. Tuesday? Wonderful…”

Sean’s looking down at the sand. He pulls his cap low and huddles under the umbrella like his stomach is convulsing.

I don’t want to say it, but I do. “Sean, what are you trying to tell me?”

He screws up his face, his eyes shifting across the blanket in front of him. “It happened again,” he says. “It happened again, only this time he did more…”

“Are you back on that? Seriously?” I cut him off. I don’t want to hear it. “You said you were joking. That was the end of it, you had your fun, now cut it out.”

“I’m not joking. I wasn’t joking.” He says this softly, without emotion.

I feel my chest burn. “Really? Except what if you’re joking now?” I get to my knees. “Let’s just swim or something.” Then I find myself saying what I almost told my mom when she announced he was coming with us. “You’re lucky I still hang with you.”

He ignores that, or maybe he doesn’t. His face changes. His eyes burrow into the sand, and he grips his knees, closes them like a vise. “Paul said I’ll like it. He said I’ll feel good and make him feel good too.” Now he opens and shuts his legs like a bellows.

“You can’t do this,” I hiss at him. I get up to my feet. “You can’t tell me it’s true if it isn’t. Are you saying he hurt you? Come on, Sean, make up your mind!”

“I don’t know. No. It doesn’t hurt.”

I’m down again. Hearing my mom’s ringtone, I peek around the umbrella. She’s kicking through the sand some way down the beach, still on the phone. “You have to tell your mom,” I whisper. “This is too gross.”

“I will. I will, but you can’t.”

“What more did he do?”

“I’m not telling you.”

I don’t know what to say. The tide has washed over the sandbar. Checking, I see my mother is off her phone now, and soon she is back with us. I clam up.

“That’s two things next week,” she says. “The newspaper might have a job for me, part-time to start, and Grandma is coming for a few days, too.”

I nod mechanically. “You wanted to go back to work there. Good. Ginny should be done with her cold when Grandma comes.”

“Oh, I hope so!” Mom says. “I’m sure.” She sits on the blanket outside the umbrella, smiling as she empties the pail and arranges her shells in sizes and colors.

“Reapply, please,” she says.

Sean is staring now. I feel his eyes on me. I know I’m not supposed to give any hint of what he just told me. I also know my mom is out of this completely, counting out her shells on the blanket. Am I supposed to fix this all by myself?

I need to think. I stand in the sun and put on another coat of lotion. Reapply. Reapply. We’ve done this for years. But today is different.

He said I’ll feel good and make him feel good too. My stomach turns. He did more.

“I’m going in the water.” I mean by myself. I step away down the sand.

“Just be where I can see you both,” Mom says, ignorant that I want to be alone. “Sean, take it easy with your pod. Are you sure it won’t come off?”

“It’s okay. It’s waterproof. But there’s always the other one, if I need it.” He opens his beach bag. “See?” His hands are shaking.

Without looking back, I run down the sand as if I don’t care about anything. I wade in for a long way before I get to my waist. Splashing my chest and arms, I feel like the water, warm in July, is washing Sean’s words off me. It feels good. As if I’m just me again. I wash him off. I dive under to get my face clean of the looks he gives me, to get his words and jokes out of my ears. I look out across the bay, away from the beach. The breeze rolls over me.

Finally, I turn.

Sean hasn’t left the blanket. He’s pretending to look around like everything’s fine. What a faker. Maybe he’s talking with my mother. I don’t know. Her eyes are closed and she’s half in, half out of the umbrella’s shade. I watch him glance over at her, then stand up slowly. He checks the seal on his pod and he runs to the water. He sloshes in, keeping his pod arm under the water, and I wonder if it really will stay on. I don’t move. I don’t want to talk to him.

But he doesn’t come to me.

He swims out away from me, both little white arms slapping the surface, his head turning this way and that like a real swimmer. I worry again about his pod. I want to yell to him about it. I don’t.

I go out only as far as I can feel the bottom a few inches under me, bouncing up and down on my toes to keep my neck and head out of the water.

Sean is in beyond his height, my height, too. A tingle runs through my chest. He bobs, keeping afloat by pushing the water down with his palms. It’s deep.

“Sean!” I call.

He stops.

He stops moving his arms. He goes completely still. His face is a small sad circle of eyes and nose and white lips, his hair short, wet, dark. I realize at that moment how far away from me he is.

Without gulping air, without making it seem like he’s diving, because he isn’t, Sean sinks.

“Hey,” I yell at him, knowing his ears are filled with water. I edge out beyond my limit, bouncing high from the bottom and working my arms and hands to keep afloat. It gets colder the deeper I go. “Hey! Sean!”

I wait for him to come back up, but he doesn’t.

He doesn’t come up. My blood runs colder than the chilly water. I swish around. We are far out, and the tide is still coming in. Turning for a half second, I can’t spot my mother right away. “Mom!” I scream.

There is a splash.

Sean’s head breaks the surface, his face a white ghost, his eyes open, his hair streaming over his forehead. I want to punch him.

“What the heck are you doing?” This is not what I really say. I curse him. Then I scream, “What are you doing?”

He sloshes noisily toward me, past me, sloppily past me. “Nothing.”

He’s back where he can touch the bottom. He’s walking now, but his pod is hanging off; the sticky seal has broken.

“You need…” I start, but don’t finish. I follow him back in. I’m exhausted by the time we make it to the sand. He drags the water heavily with him up the slope of the beach, then he stops.

We’re still out of hearing of my mother, of everyone.

“Look, I don’t care if you believe me,” he says, looking at the sand between his feet. “Paul made me do things

. I can’t tell you what. I won’t ever tell you.”

I swallow the lump in my throat. “He touched you? Down there? Is that what you’re saying? What are you saying?”

“He touched me and I touched him.”

“That’s so sick. Shay, you did not.”

“He said it was okay that we touch. And touched isn’t even what he was doing, what his fingers were doing. He said he’s moving away at the end of the summer anyway, leaving the Cape, so it’s just for a little while. You have to promise me that you won’t ever tell.”

Sean sounds as if he’s sobbing, but he isn’t. Not on the outside. Not in his eyes.

“No. I won’t do that.”

“Promise me, Owen. Because if you tell somebody—anybody—I’ll kill myself. I know how. I totally know how and I can.”

The words knife me in the throat. I’ll kill myself. Kids our age never do that. Only high school kids do that when they’re bullied. And that’s one every five years, right?

Or maybe I don’t know anything about it.

There is a look in his eyes. Even in that bright sunlight, his eyes are dark, as if all the white has drained out of them and only black irises remain. His glare swallows me and everything else around us—the color, the running children, the girls in bikinis, the families, their movements. The whole place except him just dies. He’s quivering. His outline blurs as if he’s dizzy and going to faint, or I am. I can’t even tell. The white sand turns black around us. I’m afraid for him. And for me. I close my eyes so I don’t fall over, so I don’t have to look at his face.

“It’s just for a little while. Owen, promise me. I’ll get over it. I will.” Then, water beading his cheeks and his quivering chin, he says very slowly through his teeth: “You have to promise, or I will be dead!”

“Stop saying that!”

In a whisper: “If you tell, I will kill myself!”

The k cuts again, cuts into me this time. And I suddenly remember that his father works with guns. Is there a gun at his house? My insides become water, and they want to empty out of me right on the beach. I tighten the muscles in my rear to keep it from happening. I say the words.

The Great Jeff

The Great Jeff Underworlds #1: The Battle Begins

Underworlds #1: The Battle Begins Superhero Silliness

Superhero Silliness Treasure of the Orkins

Treasure of the Orkins Queen of Shadowthorn

Queen of Shadowthorn The Knights of Silversnow

The Knights of Silversnow Underworlds #2: When Monsters Escape

Underworlds #2: When Monsters Escape Sorcerer

Sorcerer Danger Guys on Ice

Danger Guys on Ice Dream Thief

Dream Thief The Moon Scroll (The Secrets of Droon #15)

The Moon Scroll (The Secrets of Droon #15) The Coiled Viper

The Coiled Viper Pirates of the Purple Dawn

Pirates of the Purple Dawn What a Trip!

What a Trip! Moon Magic

Moon Magic Wade and the Scorpion's Claw

Wade and the Scorpion's Claw Incredible Shrinking Kid!

Incredible Shrinking Kid! Flight of the Blue Serpent

Flight of the Blue Serpent The Serpent's Curse

The Serpent's Curse Gigantopus from Planet X!

Gigantopus from Planet X! The Great Ice Battle

The Great Ice Battle Under the Serpent Sea (The Secrets of Droon #12)

Under the Serpent Sea (The Secrets of Droon #12) The Riddle of Zorfendorf Castle

The Riddle of Zorfendorf Castle Lost Empire of Koomba

Lost Empire of Koomba In the Shadow of Goll

In the Shadow of Goll Danger Guys

Danger Guys The Copernicus Archives #2

The Copernicus Archives #2 Lunch-Box Dream

Lunch-Box Dream Into the Land of the Lost

Into the Land of the Lost Cosmic Boy Versus Mezmo Head!

Cosmic Boy Versus Mezmo Head! The Crazy Classroom Caper

The Crazy Classroom Caper Quest for the Queen

Quest for the Queen The Sleeping Giant of Goll

The Sleeping Giant of Goll The Startling Story of the Stolen Statue

The Startling Story of the Stolen Statue Brain That Wouldn't Obey!

Brain That Wouldn't Obey! The Ha-Ha-Haunting of Hyde House

The Ha-Ha-Haunting of Hyde House In the Ice Caves of Krog

In the Ice Caves of Krog In the Ice Caves of Krog (The Secrets of Droon #20)

In the Ice Caves of Krog (The Secrets of Droon #20) Beast from Beneath the Cafeteria!

Beast from Beneath the Cafeteria! Mississippi River Blues: (The Adventures of Tom Sawyer) (Cracked Classics, 2)

Mississippi River Blues: (The Adventures of Tom Sawyer) (Cracked Classics, 2) The Hidden Stairs and the Magic Carpet

The Hidden Stairs and the Magic Carpet The Mysterious Island

The Mysterious Island Flight of the Genie

Flight of the Genie Voyage of the Jaffa Wind

Voyage of the Jaffa Wind Dream Thief (The Secrets of Droon #17)

Dream Thief (The Secrets of Droon #17) Danger Guys Hit the Beach

Danger Guys Hit the Beach Escape from Jabar-loo

Escape from Jabar-loo Zombie Surf Commandos from Mars!

Zombie Surf Commandos from Mars! Firegirl

Firegirl Underworlds #4: The Ice Dragon

Underworlds #4: The Ice Dragon Attack of the Alien Mole Invaders!

Attack of the Alien Mole Invaders! The Chariot of Queen Zara

The Chariot of Queen Zara The Isle of Mists

The Isle of Mists The Fortress of the Treasure Queen

The Fortress of the Treasure Queen The Moon Scroll

The Moon Scroll The Golden Vendetta

The Golden Vendetta The Tower of the Elf King

The Tower of the Elf King Crown of Wizards

Crown of Wizards Search for the Dragon Ship

Search for the Dragon Ship Wizard or Witch?

Wizard or Witch? Underworlds #3: Revenge of the Scorpion King

Underworlds #3: Revenge of the Scorpion King The Mask of Maliban (The Secrets of Droon #13)

The Mask of Maliban (The Secrets of Droon #13) The Summer of Owen Todd

The Summer of Owen Todd City in the Clouds

City in the Clouds Knights of the Ruby Wand

Knights of the Ruby Wand Danger Guys Blast Off

Danger Guys Blast Off Danger Guys and the Golden Lizard

Danger Guys and the Golden Lizard The Magic Escapes

The Magic Escapes Mississippi River Blues

Mississippi River Blues The Crown of Fire

The Crown of Fire The Golden Wasp

The Golden Wasp Voyage of the Jaffa Wind (The Secrets of Droon #14)

Voyage of the Jaffa Wind (The Secrets of Droon #14) Denis Ever After

Denis Ever After In the City of Dreams

In the City of Dreams The Moon Dragon

The Moon Dragon Revenge of the Tiki Men!

Revenge of the Tiki Men! The Hawk Bandits of Tarkoom

The Hawk Bandits of Tarkoom The Postcard

The Postcard The Copernicus Legacy: The Forbidden Stone

The Copernicus Legacy: The Forbidden Stone The Knights of Silversnow (The Secrets of Droon #16)

The Knights of Silversnow (The Secrets of Droon #16) Under the Serpent Sea

Under the Serpent Sea Voyagers of the Silver Sand

Voyagers of the Silver Sand X Marks the Spot

X Marks the Spot The Crazy Case of Missing Thunder

The Crazy Case of Missing Thunder Journey to the Volcano Palace

Journey to the Volcano Palace The Hawk Bandits of Tarkoom (The Secrets of Droon #11)

The Hawk Bandits of Tarkoom (The Secrets of Droon #11) The Race to Doobesh

The Race to Doobesh Trapped in Transylvania

Trapped in Transylvania Humbug Holiday

Humbug Holiday Goofballs 4: The Mysterious Talent Show Mystery

Goofballs 4: The Mysterious Talent Show Mystery The Mask of Maliban

The Mask of Maliban Final Quest

Final Quest The Genie King

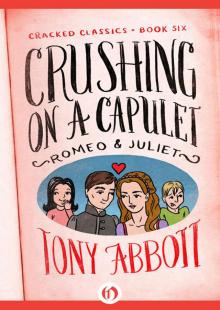

The Genie King Crushing on a Capulet

Crushing on a Capulet